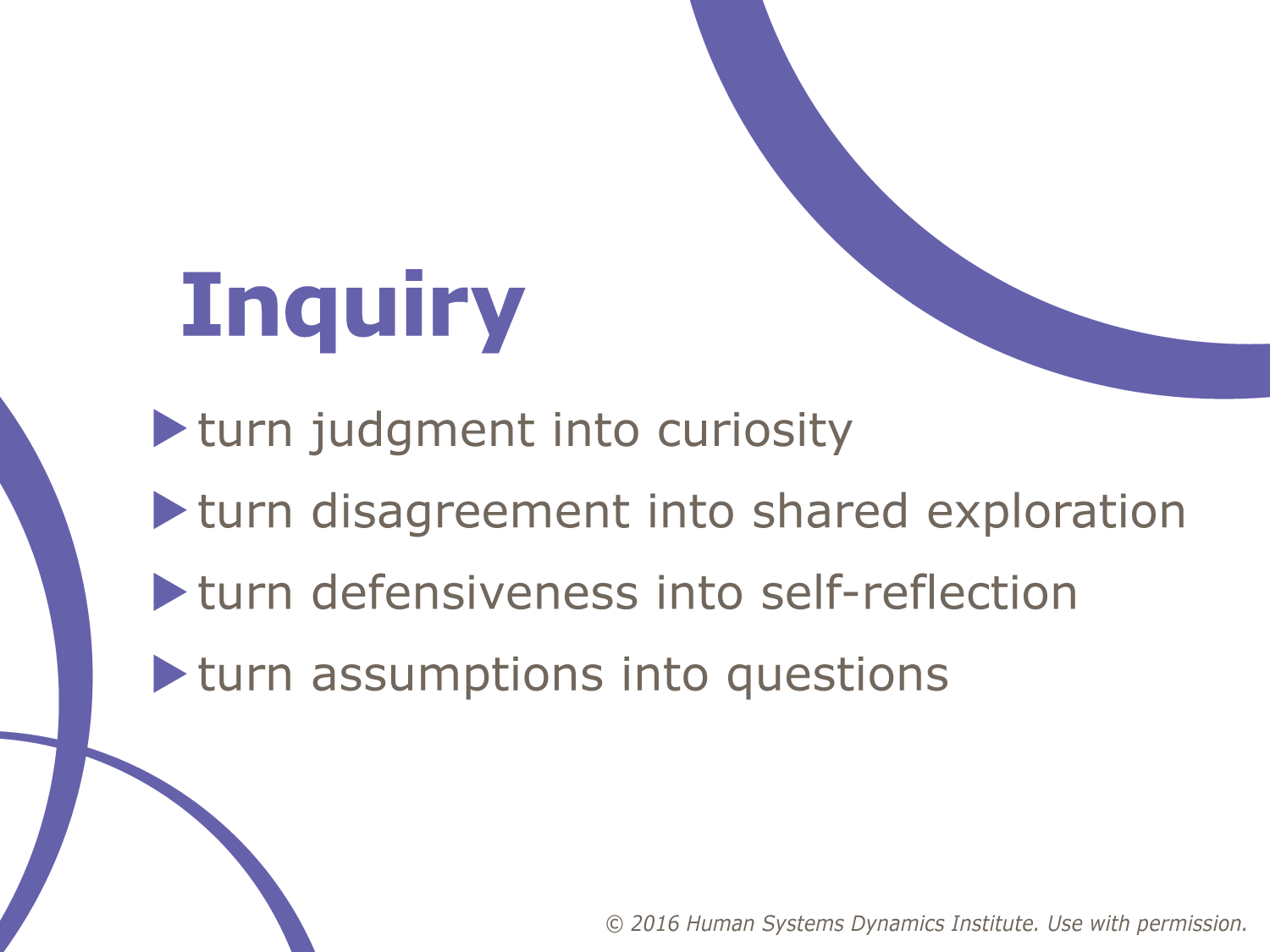

Inquiry

When you stand in inquiry, you exhibit patterns of behavior that help you see, understand, and influence your world.

Inquiry is about questions. It is approaching every interaction, every situation, every opportunity with questions about what can be learned in this moment, in this situation, with this person. In the emergent, unpredictable world of complex systems, inquiry is the only way you can move forward.

What is inquiry?

-

What?

Standing in inquiry enables you to gather information you need to see, understand, and influence patterns of interaction and decision making that shape your world.

-

So what?

You gather information from your environment to make decisions and take action in your world. Standing in inquiry enables you to see clearly and remain open to the reality around you.

-

Now what?

When you stand in inquiry, you exhibit patterns of behavior that help you see, understand, and influence your world.

How do we know we stand in inquiry?

What is the purpose of inquiry?

In times of complex, unpredictable change, questions show you a way forward. Use the stance of inquiry to create your future out of chaos.

How to adopt the patterns of inquiry?

Succeeding in complex environments requires adaptive capacity, and adaptive capacity requires that you step into and stand in inquiry. Inquiry is most powerful when it is not just a way of working with clients and not just a path toward professional learning. Engaging the world through a lens of inquiry is to engage with curiosity to be your best at work, at home, in politics, in service. Inquiry becomes a way of life. Using inquiry to build adaptive capacity is not just about asking questions. It is approaching every interaction, every situation, every opportunity with questions about what can be learned in this moment . . . in this situation . . . from this person.

Turning judgment into curiosity

Judgment allows us to discern what we like and don’t like, what is safe and what is not, which path will more likely take us to our destination. Judgment helps us avoid what is dangerous and stay safe. Other times judgments limit what we can see, shaping a landscape of decision making and action that is too narrow to support and sustain learning and adaptation.

Patterns of bias and prejudice are cultural examples of judgment that focus on differences that restrict, rather than encourage, growth.

When you recognize these types of behaviors in yourself, the best thing to do is to stop, take a deep breath, and ask yourself some questions.

► What if that were not so?

► What else might be possible if. . . ?

► What is this person really saying?

► What else?

Turning disagreement into shared exploration

When you engage across the differences to understand what they are, you can dissipate the energy that drives the disagreement by turning it to shared and mutual interest. You listen more deeply; you look for points of convergence; you turn your judgment into curiosity:

► What would it be like if we . . .?

► What is it that makes this so “awful” for each of us?

► What nugget of shared benefit can we find?

► What else?

Patterns of disagreement emerge whenever we encounter difference. “Things are not as I believe they should be.” “Others don’t see things as I think they should.” “This should not be happening.”

Patterns that emerge from a brush with difference can range from mild cognitive dissonance to argument to conflict to all-out violence and war. In complex systems, difference is not destructive, it is the energy behind all change.

The greater the difference, the greater the energy for change, the greater the potential for larger and more impactful patterns.

Turning defensiveness into self-reflection

When the threat comes, our first reaction is to get it and all it represents as far away as possible. What might happen, if, at that moment, we stopped and reflected on why we feel as we do?

When we feel threatened, we may need to move to a place where we are safe from harm. At the same time, what feels threatening may come from our own perceptions of the situation or the people in it. The fear we feel may very well be about our own sense of safety or status or competence, for instance, and the only way to “move away” from that sense of danger is to reflect on what that fear represents to us.

When we can separate the real threat or danger from our own perceptions and personal fears, we are better able to step beyond the flight-or-fight response and engage across that difference.

The next time you feel such a threat, stop yourself and ask:

► What about this feels familiar?

► What am I afraid of losing, and how can I step beyond that and see the other person’s perspective?

► What am I telling myself about what just happened, and what might be an alternative explanation?

► How would others describe what just happened?

► What else?

Turning assumptions into questions

Our assumptions provide the foundations for how we see and understand our world. They shape our perspectives and give us a conceptual place to stand. From that space, we step into decisions, choices, and actions that shape our life.

Our assumptions are based in our experiences and in the lessons we have learned through the course of our life. Our cultural background, our family or community values, experiences of joy or pain, and our sense of self inform our assumptions about the world.

Sometimes our assumptions are built on fact and reality; sometimes our assumptions are not. They may be based on misinformation or lack of information or misinterpretation of the information we have...

When you are stuck and don’t know what to do, it may be because some underlying assumption prevents you from seeing the situation clearly. Your assumptions can limit your ability to find new options for effective and meaningful action.

When that happens, take a moment to consider how the assumptions you hold constrain your perspectives and opportunities:

► What do I believe about this situation and how are my beliefs holding me in this pattern?

► What other ways might I think about this pattern to shift my current experience?

► What assumptions do other people hold that might inform my decisions differently?

► What else?

“We find that answers have a pretty short shelf-life. By the time you get to the next question, the answer you formulated earlier may not continue to hold true.”

- Glenda Eoyang